Who better to close our Black History Month feature than with this militant centenarian. Tim Black rubbed shoulders with the greatest figures in 20th century Black History: political leaders and jazz legends jostle in the memories of the Chicago-born “griot”.

It’s not every day you turn 100. And in the case of Timuel D. Black, the moment was at the height of his testimony which occupied a century in the heart of Chicago’s South Side. This is what Reverend Jesse Jackson recalled during the symposium organized at the end of 2018 for Tim’s centenary celebrations. He was not the only one to celebrate him, receiving that same day the French Legion of Honor for the role he played during the liberation of France in World War II! A former social worker of the same neighborhood whom he had previously helped, Barack Obama, also sent him a warm birthday message. He remembered their first meeting, a few days after his arrival to Chicago in the early 1980s. “We sat opposite each other: on one side, – me – the new recruit, and on the other, the veteran historian. And as early as that first conversation, I learned a lot from Tim, from his deep empathy… His desire to improve people’s lives across the city and to achieve greater equality inspired me.” Poet Useni Eugene Perkins called him “the Bronzeville Griot”, referring to one of Chicago’s historic epicenters in the African-American community. The title is in no way assumed for such a storyteller who, having been born on December 7, 1918 in Birmingham, the infamous city of Alabama, lived his whole life in the south side of Chicago – in the heart of one of the USA’s Black consciousness’ matrixes. And deep within the music that expressed it so well.

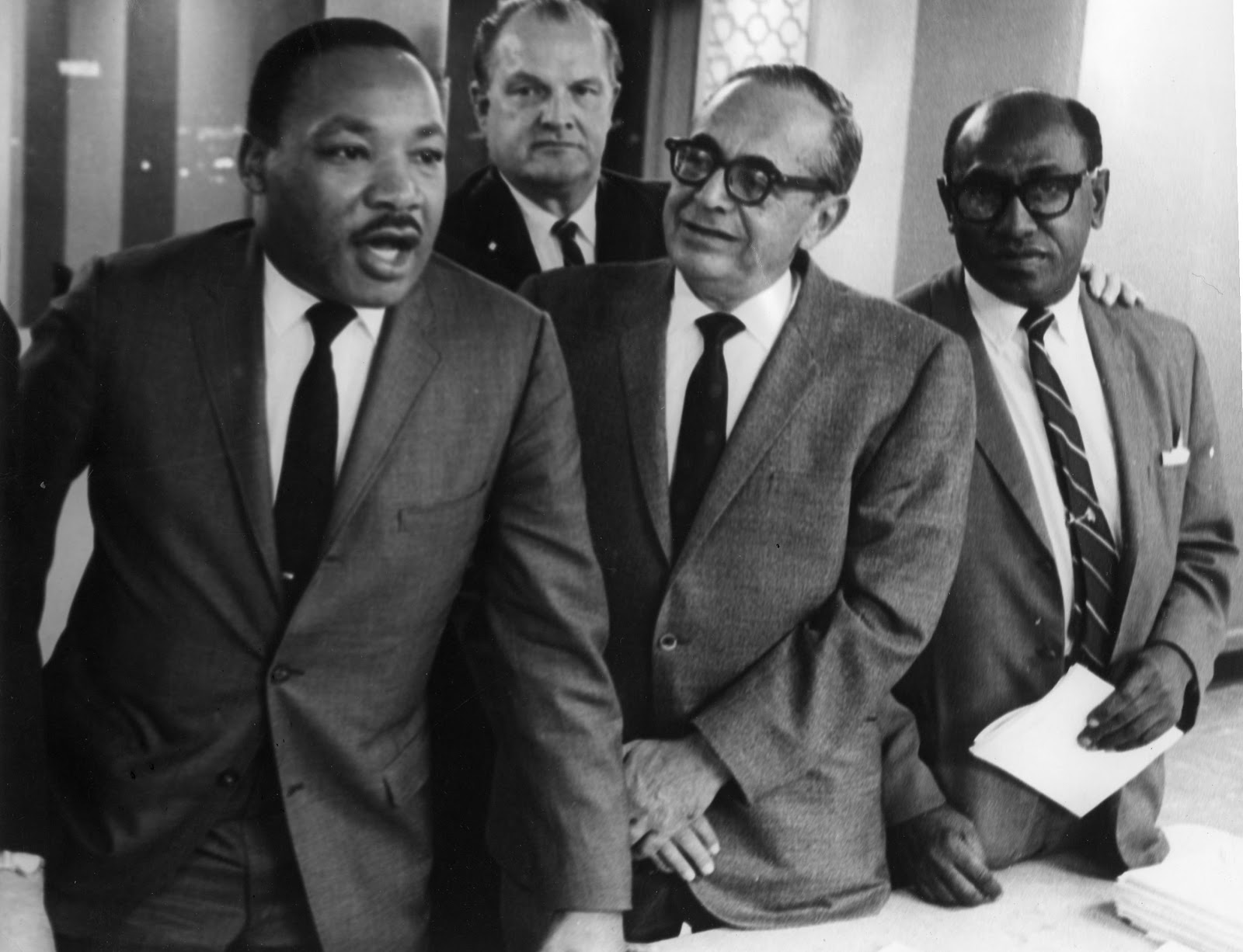

Tim Black, Dr. Martin Luther King (1965) – Chicago Public Library

100 years of struggle, 100 years of jazz music

He had not yet reached one year of age before his parents deserted the Deep South – the lynching land where his grandparents were slaves – to end up in the Black Belt, which had recently been a scene of violent riots. These would not be the last for this tireless civil rights activist.

More than just a witness to a century of struggles, this peaceful warrior was a major player for the era, meeting with important leaders in the fight for freedom, such as Socialist bard Paul Robeson, who challenged White liberal power through his playwriting abilities, and WEB Dubois, Pan-Africanism’s indispensable philosopher. And then, a few years later, Martin Luther King, whom he eventually met in 1955 in Montgomery, in his native Alabama, after having discovered him on television. “With such courage and charisma, he was the kind of leader I wanted to follow.” The following year, he invited him to come and plead the cause in Chicago. “Working alongside him was a wonderful experience. This brilliant young man, who spoke clearly, was determined to make changes, all this in such a way that he thwarted all opposition. What could they do, or respond with, when – after beating you up – you told them, ‘God bless you’?”.

In March 1963, as president for Chicago in the Negro American Labor Council, Tim Black became deeply involved in The Great March on Washington. Twenty years later, building on the independent and progressive Black political movement he initiated, he actively supported Harold Lee Washington’s running for office, as the first Black mayor of Chicago.

Tim Black, Harold Washington (1983)- Chicago Public Library

Reviewing every great moment in history in which Tim Black appears would take forever, and he chooses not to feign humility. “You know, when you are 100 years old, your memories play tricks on you.” He did not forget anything however, especially not the vision of horror he endured when he and his fellow soldiers liberated Buchenwald Nazi concentration camp: one does not come out unscathed from this kind of experience into the depths of (in)humanity.

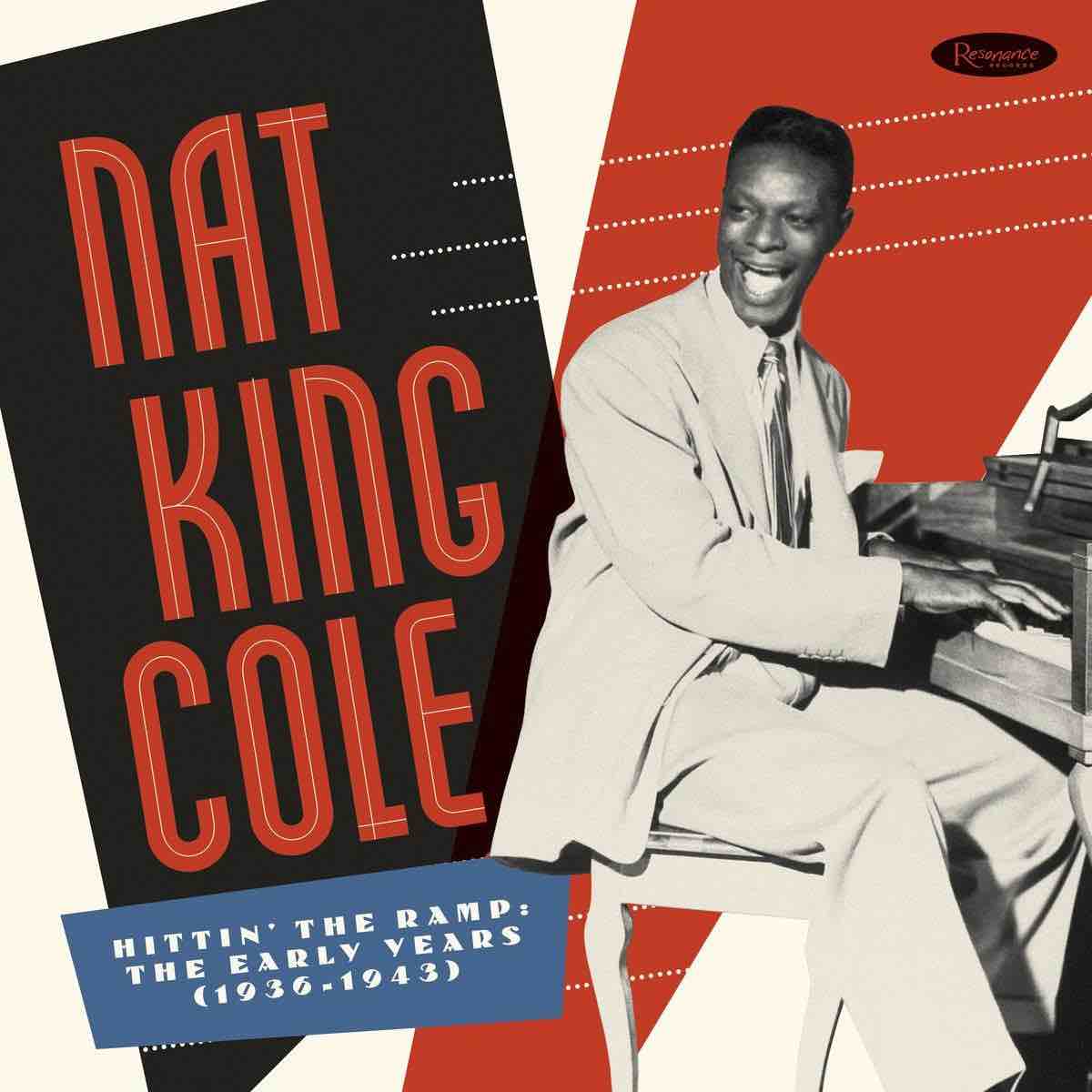

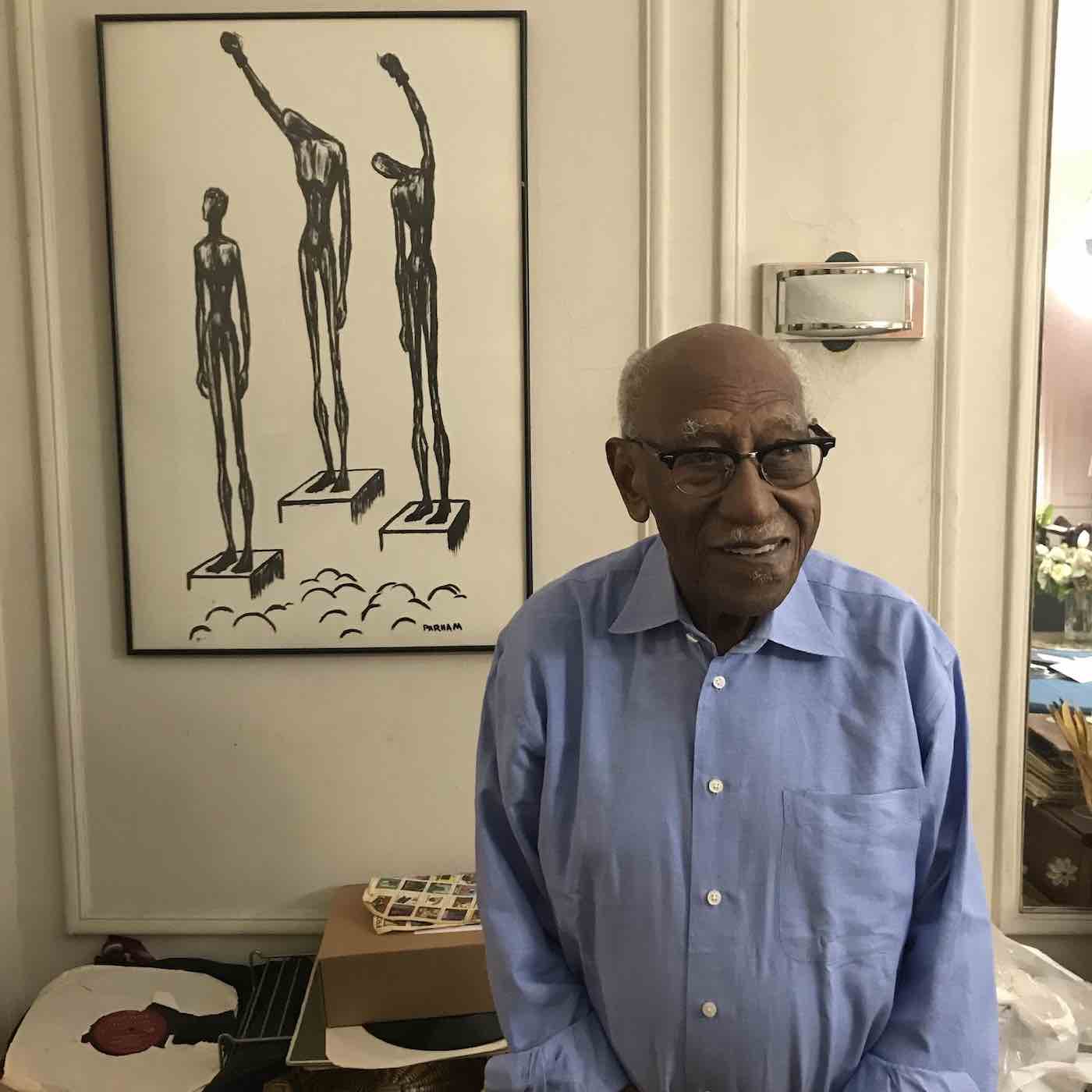

It is noon on a Sunday with mass having just been delivered when Tim Black welcomes us in slippers at his apartment, the upper floor of a house in the heart of Chicago’s South Side, not far from the neighborhood surrounding Hyde Park, undergoing heavy gentrification. His house is filled with the spirits of heroes welcomed in a busy life, starting with those of the music world. It wouldn’t be any other way for the privileged witness to the birthing hours of jazz, in the city that has come to be the birthplace of all great Black music. “In the neighborhood, this music has made it possible to unify people beyond questions of race, age and gender. Jazz brought together a diverse community both economically and racially: people of the Black Belt as well as those of the Loop [the skyscraper-saturated downtown area; editor’s note],” remembers the one who still remains a member of the board of the Jazz Institute, the institution he co-founded a little over forty years ago. “Gospel and all religious music also played an important role for all of my generation. Sunday was a blessed day for music. It was at church that most of the instrumentalists learned music.” But it was at school – first the Wendell Phillips college then the Du Sable College (named after the mixed-race founder of the city) – that he would score points with the future great African-American star Nat King Cole, but also John Johnson, who would soon launch the magazines Jet and Ebony.

“Nat King Cole was sitting right behind me. He was damn brilliant, and part of his inspiration came from Earl Fatha Hines, also from Chicago. He could have turned into a very inspired classical pianist, but the law did not allow him to! In any case, believe me, as soon as the teacher was out, everyone came into the classroom to listen to him. At the time, every room had a piano.” Tim Black would try his hand at the alto sax, being fascinated with Johnny Hodges. In vain, as he was more gifted at basketball. “My mother played the piano, my brother played the violin, I’ve always only had my ears…” And those ears must have heard a whole lot of stories. “I have often seen Ellington perform on stage. The first time, I guess I was in elementary school, and it was there that I discovered Johnny Hodges! Duke was a great universalist.” Universalism, without distinction of race, gender and class, remains Tim Black’s key philosophy, as a fervent believer of the Unitarian Universalist Church (one of Chicago’s historic congregations, which includes pantheists, pagans, agnostics and even atheists!). While reminding us of the fact that Duke Ellington could play downtown, but was not allowed to sleep there after the show.

It was also during the interwar years that Tim Black encountered Louis Armstrong more than once. “He had been encouraged to come to Chicago by a neighbor, the barber Mr. Smith, a New Orleans-native like him. Several times Armstrong came to see him and I remember that one day, with the neighbor’s children, he took us to the movies! At the time, there were many theaters like the Regal Theater, around 36th St. where everything was happening. We had our own nightclubs. In the Black Belt, racial segregation was very strict, which allowed us to have our own institutions and businesses, completely independent from White people. In this confined and physically constrained environment, music helped to develop a feeling of solidarity and resilience. It united us. The words, the rhythm… Doctors, lawyers, workers, all together. Every one of us hoped that brighter days would come.” Optimism remained one of his key survival tools to move forward.

When jazzmen began to change their mentalities

It was also in this divided area that he enjoyed Bessie Smith’s music as well as Benny Goodman’s, the latter being exemplary, according to Tim Black. “Benny Goodman had a quartet with Lionel Hampton and Teddy Wilson, and he often performed on the South Side. He showed us the way: in no way would he stick to ethnicity issues only. I’ve seen the change in mentality that happened through music. I lived it! Musicians are interested in artistic things, not racial matters. Being inclusive is the strength of this art.” He would not forget the date of this famous Goodman show. “It was the evening when Joe Louis was going to be crowned world champion! What a night! We all sang: ‘The champion is a Negro who has knocked out a German’.”

Tim Black – Photo Jacques Denis

For Tim Black, during all this time, jazz remained one of his best remedies in never ceasing to believe in a better tomorrow. “I drink a small glass of wine every day, and listen to good old jazz before I go to bed,” he smiles, with a keen expression in his eyes. His old record collection reminds us that we are in Chicago. “This city popularized and universalized our music.” Ramsey Lewis, as well as Herbie Hancock, are in fine company amongst these records… The pair embodied post-WWII jazz, an international conflict he participated in as early as 1943. “Jazz was the soundtrack for the army, which made it possible to endure combat, in the madness they called war. Then we discovered Europe, we saw Josephine Baker on stage… It clearly opened our eyes to our war-saturated reality.” Back home, like many others, Tim Black organized himself to claim rights, with the second wave of emigration that had come to the city, this time hailing from the South’s deep countryside, hoping to escape the worst of the segregation regime. “Their culture was very different: more anchored in the countryside than the first wave, also from the South but not from the big cities. That’s what gave Chicago the blues color we know today.”

This second wave of migration did not come without consequences, according to him. “The nature of Bronzeville changed during this period. We have spread our culture to other areas, but at the same time, the historic heart of the Black Belt has lost its creative force – I mean there were fewer clubs. So people had to go to other neighborhoods, downtown included, in the Loop, to listen to our music.” A long-time follower of his own community, Tim Black indicates that these profound changes in the nature of jazz are a result of the demographic upheavals that Chicago had been experiencing. “During the 1950s, land segregation was less prevalent, which allowed certain local people, of my generation, to move out. The real selection that was taking place had become a financial one. My family, for example, moved to Hyde Park, a more mixed neighborhood, leaving the old Black Belt’s ghetto. From there, the wealthy lived with the White middle class, which enabled integration. You can’t dissociate an artistic creation from its environment, where the neighborhood that Nat King Cole grew up in was no longer the same. Besides, if jazz after the 1950s was still popular in the city, it had definitely become a universal thing since the end of the war.”

For a long time, this informed pedagogue, having spread the word in numerous schools on the South Side, has believed in the virtues of the transmission and preservation of heritage, which allows for the perpetuation of the historical continuum for younger generations, both Black and White. “Cooperation is essential to build our future. New technologies unfortunately tend to isolate us and further weaken the sense of belonging to a community.” The 100-year-old man is hardly deluded about the current social situation, and despite his great age, remains attentive about the police brutality and the economic oppression that weighs on the less fortunate minorities even more. It’s also for these people that the old griot persists in telling his story. “My own story gave me hope that tomorrow would be a better day. “

Sacred Ground, Susan Klonsky, Northwestern University Press, 2019

Black History Month episodes: